A personal story about Hong Kong

I lived in Hong Kong for nine years and three months.

I married the love of my life six years in; our daughter was born a year later at Matilda Hospital on the Peak. We were frequent and unreliable tour guides to visiting friends, siblings, parents, in-laws, overseas colleagues. I started four new jobs; we moved apartment five times. Every junk trip we went on someone turned seasick green and it wasn’t me. I got my first beer belly and my first gym membership. Was a permanent resident wafting through the gates at Chek Lap Kok. My wife always took the minibus or tram I avoided at all costs. We hung out with colleagues on Tong Chong Street. Preferred Park N Shop to Wellcome. Frequented two Causeway Bay bars where they knew our names. I sweated buckets in weekend shorts & flip flops; wore jumpers in shivery office air conditioning. Shouted at taxi drivers who shouted back. Grin & bore dim sum; had a favorite Japanese, Italian, Mexican, Thai restaurant. I was a Cathay Pacific Gold Card holder. I lost my Octopus card on a regular basis. We celebrated various New Year’s Eves and birthdays in Kowloon, Tai Hang, Macau, DB. Ate seafood on Lamma, drank ale in TST, got sunburnt at Repulse Bay, shopped Apple at IFC, hiked & dehydrated on the Dragon’s Back.

Hong Kong was good to me, to us, and I, we, took it for granted in return.

But that Hong Kong no longer exists. It has gone.

—-

I know, I know. While I wasn’t a banker wanker on Lan Kwai Fong, I was still undeniably an expat. And it is not for me to decide anything about Hong Kong’s present or future. But isn’t that exactly the point – it should have been up to the 7.5 million residents to decide.

And while I don’t need to justify my interest, a little history goes a long way.

When I first visited back in 1994 on a (pull a face) gap year, I admit it: I heartily disliked the place. There were some mitigating factors – one, I’d just had the time of my backpacker life in Thailand and being too young, too idealistic, Hong Kong felt too commercial, too brash. Two, one of the thousand mozzie bites I’d been selected for in Chiang Mai had become infected and I was hobbling like an old uncle. And lastly, on top of everything else, there was an ex- who might or might not have been there from England who started to haunt every bar and street corner.

I do wish now I’d appreciated the pre-handover weirdness a bit more – the ridiculous “British” bobbies in their khaki shorts, the city within a city of Chungking Mansions, the white knuckle ride that was Kai Tak, where you could reach out and touch the hanging laundry as you flew past.

But fast-forward seven years, arriving from Jakarta in summer 2001, coming up on 30, it felt like a ‘mature’ option. We were consciously trading the authenticity of Indonesia – occasionally dangerous, sometimes fun, oftentimes heartbreaking, always stinking hot – for the convenience & efficiency of Hong Kong. We settled in just fine.

Hong Kong seemed to rebrand itself on a continuous basis – always jockeying with Singapore for being the most free (in an economic sense) city, and also for the stupidest slogans. After the decimation of SARS, millions of HK$ were spent on BrandHK who were intent on advertising Hong Kong back to the world under the clunky banner of “Asia’s World City”.

But it did feel that you could get all the vibrancy & immediacy of Asia life with some of the edges taken off. Reliable internet, hyper-efficient transport, safe streets. There were small but significant film & literature festivals. Bledisloe Cup rugby, the Cricket Sixes, preseason Premier league teams. And we could reach out beyond, weekends to Taipei, Manila, holidays in Malaysia. I still found it stubbornly unloveable but it slowly & certainly became home.

—-

In my first job there, a dispiriting trudge around factories and offices stealing their lunch hours/drinking time with my fruitless English lessons, I met someone I’ll call June. A native HongKonger, with a family backstory of fleeing from the mainland during the revolution years, June was an executive working for a major US food distribution company, and took the hour with me to hone her English debating skills. And we always ended up debating the same things – what was Hong Kong, and what was Hong Kong’s future. Deep within her serious and seriously aggressive manner was the idealistic hope that Hong Kong could, perhaps, teach the mainland, as China was always called, as it slowly emerged on the world stage. She had a family’s anger at the absence of manners & respect mainlanders could show, and thought (however unpopular this idea is) that while there had been a lot wrong with the British, there had been (wince) a civilizing influence – in society, the courts, and politics.

True to say that too much of Hong Kong’s success has been left at the Brits door. Hong Kong was still a hugely corrupt & volatile place for a big chunk of the middle 20th century under this so-called ‘civilising’ British rule – and there were many instances of corrupt Brits profiting from the murk. It probably wasn’t until the formation of the feared Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) in 1974, when things started to change, and even then, slowly. No, Hong Kong success is all about HongKongers with their no-nonsense drive, their entrepreneurial guile & gambling spirit, and their incessant & entirely pragmatic search for a deal – with Westerners, Asians, Communists, capitalists, Buddhists, you name it, let’s get it done.

To me, Hong Kong has always been a Chinese success story. So what happened next can only be a Chinese tragedy.

—-

Sun Tzu would be impressed, as might (shh) that old general Chiang Kaishek. The eventual crackdown on Hong Kong used an age-old technique: turn an opponent’s strength against them. So the powerful “civilising” apparatus – the courts, the civil service, the (pliable) legislature, the now incorruptible police – once co-opted, could be used against the pro-democracy movement. All China had to do was change the laws. Which they promptly did.

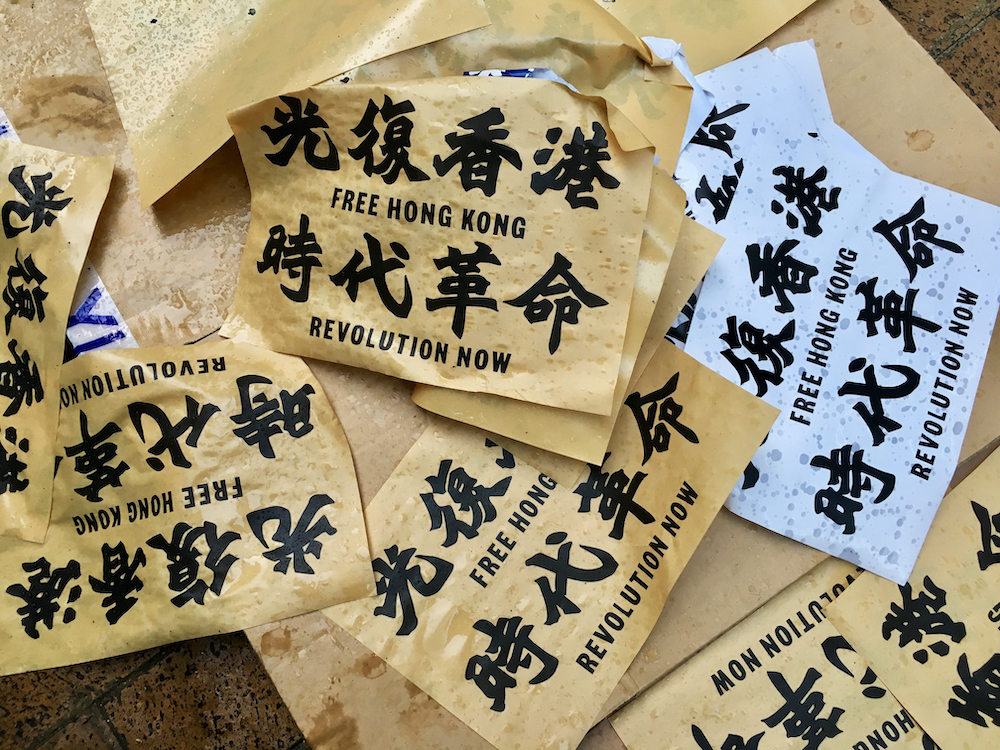

Some may feel these were rather ‘technical’ changes – new laws, revamped electoral rules, etc. The People’s Army, after all, didn’t roll into town in tanks to crush the People. But the end result was the same. Gone are Hong Kong’s freedoms, and therefore, gone is what makes “Hong Kong” exist as an idea. If the people can’t protest then the people are silenced. And a silent city is controllable, a manipulable city of the state – another Shenzehn or Chongqing.

It’s no great insight to make the point that China’s policy resembles nothing better than a version of war’s notorious ‘scorched earth’ concept, as demonstrated with Kurt Vonnegut levels of insanity in Vietnam. The crazy logic: the best way to save a place, is to destroy it. I can’t help feeling it’s also fuelled by a weird sense of envy, like an older sibling taking to task a wild & rebellious sister whilst all the time clearly wishing they could be Just. Like. Her.

Let’s not sugarcoat it, there were/are numerous issues in real-life Hong Kong. A property-based economy enforces crippling income inequality; the treatment of overseas help is often scandalous; there are numerous ‘quality of life’ issues from pollution, noise, and neglect. And, somewhat ironically, its treatment of mainland Chinese tourists who help fuel the economy can be pretty disgusting.

But “Hong Kong” also existed as a geographical and cultural experiment, and somehow found a unique spark for success. A spark that could have been cherished, and maybe even used to light fires in other China cities. To snuff it out through spite and insecurity is a real tragedy for both Hong Kong and China. Because it can’t be conjured up again.

—-

Like a cloud falling across the sun, something was passing – from before to after, from fight to defeat, from Hong Kong to What Have We Become.

I was last in Hong Kong in late October 2019. While sitting at home watching streets I knew so well turn into battlegrounds was worrying, I was reassured by the folk who lived there. The protests had seemingly simmered down from their ferocious worst and unless the airport was going to be shuttered again, none of it seemed enough to actually stop me going. Though I will admit to being momentarily spooked to see my hotel, tucked away from the action, or so I thought, next to a Taikoo Shing mall, suddenly appearing on BBC News in the Heathrow departure lounge. Of course, by the time I arrived the next day every single sign of disturbance had been swept away, and the mall was bustling.

So Hong Kong was, on the surface, as Hong Kong always is – efficient, noisy, belligerent, unconcerned. But talking to friends and colleagues there was a weary jitteriness. To be clear, not all were for the continuation of protesting. One, in particular, was rather virulently and, in his eyes, patriotically pro-China (and, by logic, pro-police). But everyone could agree that the impasse had to break one way or another – a continuation was impossible. All the talk of the time was of whether Carrie Lam would make some concessions, or be removed. No one really talked about their freedoms being removed from 2,000km away. How people would then be prosecuted and found guilty for peacefully protesting. How the ‘thought crime’ of pro-democracy would get you carted away in the back of a police van, press cameras flashing.

And sitting in that late fall sunshine, looking out at the harbour, surrounded by friends, there were still flashes of the place I recognised. In true Hong Kong spirit, various apps had sprung up to warn locals about demonstrations and transport blockages. And in even truer Hong Kong spirit, everyone was simultaneously trying all of them, and were engaged in constant argument about which one was best.

But there was also a gathering sadness. Both expat and native HongKongers spoke to me about moving away. Like a cloud falling across the sun, something was passing – from before to after, from fight to defeat, from Hong Kong to What Have We Become. It wasn’t as dramatic as the fall of Saigon but the future had never looked less certain. I’d had a peaceful week but still flew away with a heavy heart. A week later, despite me telling everyone on my return it was being overblown, all hell broke loose once again. The final chapter had begun.

One day, I’ll go back. My daughter has yet to see her birthplace after all. But I don’t know where we’ll land because Hong Kong has gone.